“That Öcalan is still in jail after 25 years, and remains incarcerated 45 years after he started the movement, is equivalent to the lack of freedom the Kurdish people still live under. They cherish him because they have grown to cherish themselves. His freedom is their freedom.”

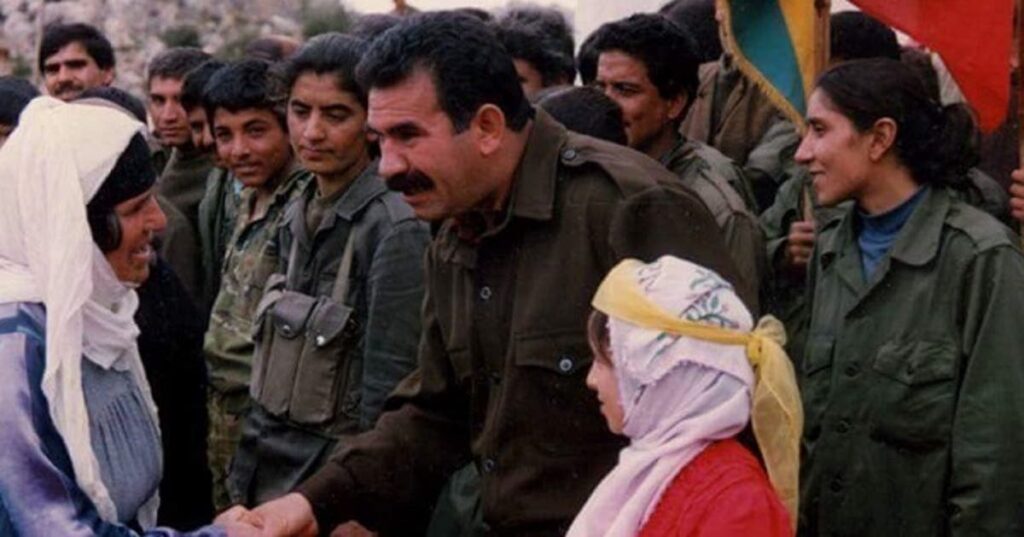

You could go ask the guerrilla fighters who fight their struggle in his name why Abdullah Öcalan is so important to them. Well, you can’t really do that now because a Turkish drone would assassinate you if you entered PKK territory in the mountains in Başur (Kurdistan in Iraq), but it’s what I did a couple of years ago. What I received as answers ranged from a lyrical hymn to a rather sober ‘dear older brother’ kind of explanation, but all the answers combined still help me to profoundly understand the Kurdish movement’s insistence on his freedom.

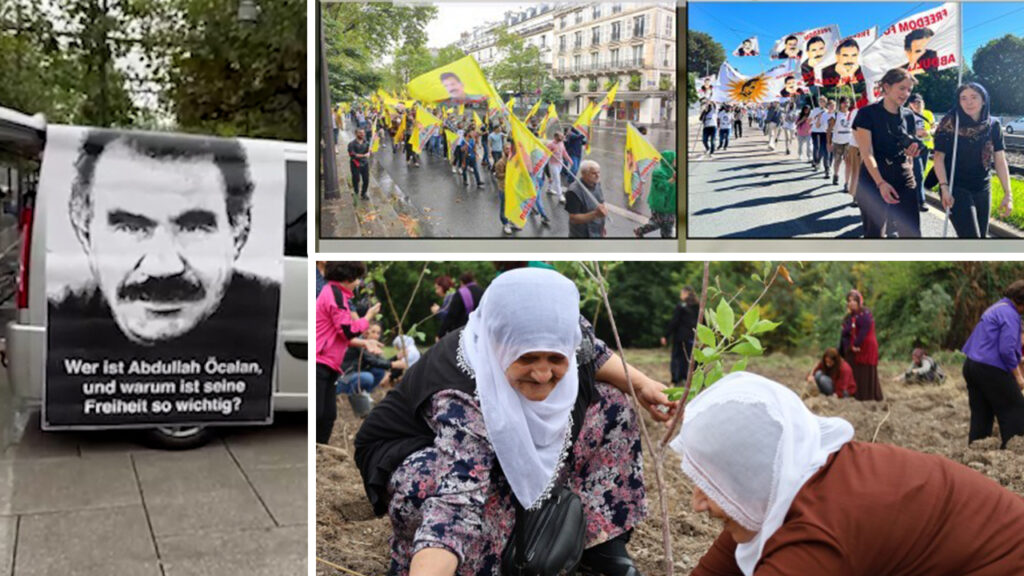

It’s been a quarter of a century since Öcalan was captured in Nairobi, Kenya, in an international plot. On 15 February 1999 he was transferred to Turkey and locked up in the prison where he remains behind bars up until today. Twenty five years in captivity. He might as well have been forgotten. He might as well have been overshadowed by new Kurdish leaders, or his ideology been rendered out of date in the fast-developing 21st century. But the opposite is true. His importance has only grown.

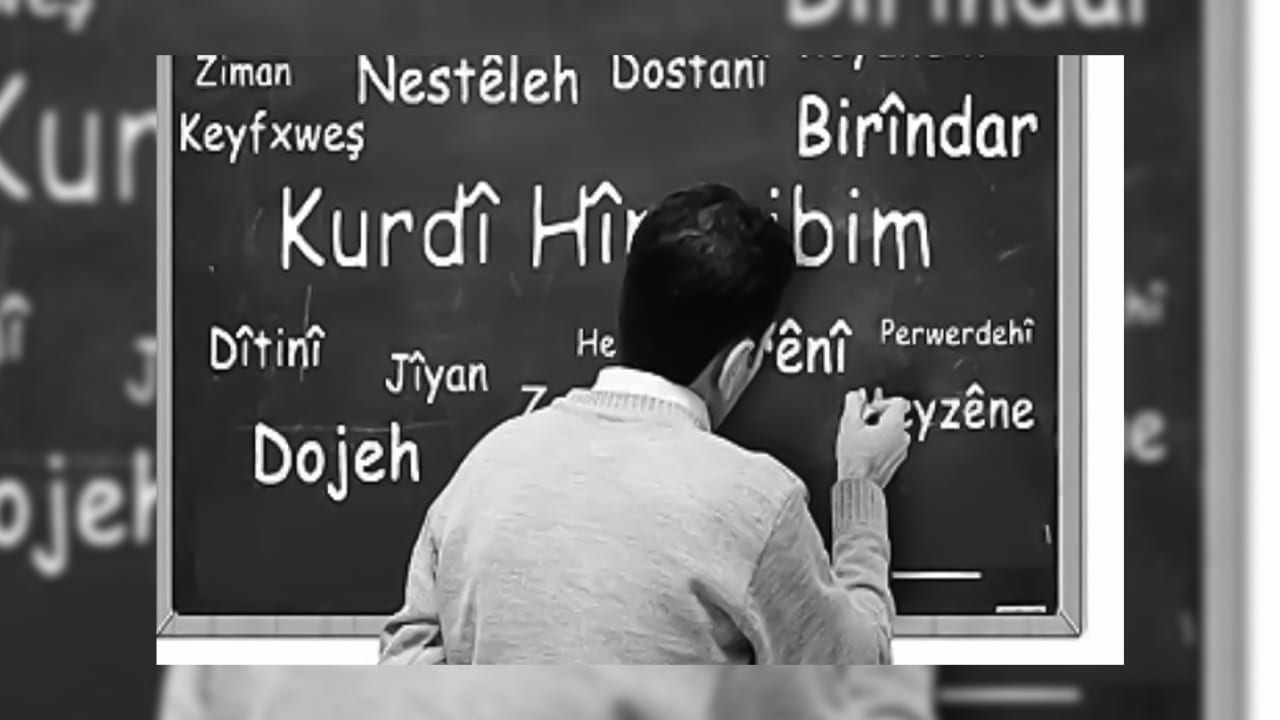

Mothertongue

Guerrilla fighters who are of Öcalan’s generation and who are in their 60s and 70s now, among whom the co-leader in the mountains, Cemil Bayık, testified to me about the early days of the PKK in the 1970s. After many decades of forced assimilation by the Turkish state and several mass murders and violent suppressions of rebellions, many Kurds were not aware anymore that they were Kurdish. Even Cemil Bayık was not aware of his Kurdishness at the time. He, like many Kurds, didn’t speak his mothertongue.

Öcalan changed that. He led the small group of people who founded the PKK in 1978. They were rooted in the Turkish leftist movement, but contrary to the beliefs of Turkish left, they believed that the liberation of Turkey started with the liberation of Kurdistan – a word that could not be uttered, and is still highly controversial in Turkey today.

What Öcalan did, you could say, is revive the Kurds from their decades-long slumber. Thanks to his leadership, they came to life again as Kurds. Being Kurdish changed from something to hide or deny or something to be ashamed of into a source of pride. Something to fight for. Something to live for.

Gratitude

The interesting thing is, this gratitude to Öcalan was also prevalent among young fighters. This may surprise you, as it surprised me. Well, to be honest, it annoyed me a little bit. Some of the PKK members who had recently joined and were around 20, 25 years old, just couldn’t get enough of the phrase ‘Serokatî got’ whenever I asked them something. ‘Serokatî got’ means ‘The leadership said’, the leadership obviously being Öcalan, and it would be followed by some saying or truth. Why were they clinging to Öcalan after having grown up fully aware of their Kurdishness? Why would they refer to him even for the most basic things, for example even when it came to, say, cleaning the kitchen in a forest camp?

I received a very insightful answer from comrade Nûman, a guerrilla fighter who was in his 40s who had joined the PKK as a young adult himself. I quote him literally – it’s a quote from my book about the PKK (This Fire Never Dies,): “Using ‘Serokatî got’ is a sign of weakness. The young haven’t started thinking for themselves yet. It’s understandable. You can compare them to newborn babies. They still feel a deep connection with Öcalan. It is up to us, the more experienced fighters, to slowly cut this umbilical cord and teach them a more mature and independent way of thinking.”

Dignity

The young generation in the mountains start their lives anew too when they join the armed resistance. They no longer live in the fascist state, which continues its forced assimilation efforts and continues to murder, prosecute and jail Kurds and deny them their rights, but start a new life in Kurdistan. A sense of belonging, and a sense of pride to fight for the survival and dignity of their people. Born for the second time, and starting to grow up. The metaphor of the umbilical cord is very interestingly chosen.

You could apply this to the Kurds as a nation as well. They had resisted the state’s violence in the first two decades after the foundation of the Turkish Republic in 1923 but paid a high price at the hands of a brutal army. The foundation of the PKK was the first successful resistance in decades. Kurds started to come to life again. They stopped hiding their identities, started living their culture without shame or fear, educated themselves and built on the resistance of their ancestors.

Freedom

It was dangerous and they were putting their lives on the spot, but for a bigger goal. The stronger they grew, the more independent thinkers they became and the more new leaders the movement birthed. But they never lost the firm connection to the man who had founded the movement that gave them life. On the contrary. The umbilical cord has long been cut, the Kurds are mature but the source of that life won’t ever be disregarded or denied. It will be cherished.

That Öcalan is still in jail after 25 years, and remains incarcerated 45 years after he started the movement, is equivalent to the lack of freedom the Kurdish people still live under. They cherish him because they have grown to cherish themselves. His freedom is their freedom.

Leave A Comment