Art as resistance: exiled Kurdish artist’s daring Istanbul show

Art as resistance: exiled Kurdish artist’s daring Istanbul show

- Date: November 10, 2020

- Categories:Culture

- Date: November 10, 2020

- Categories:Culture

Art as resistance: exiled Kurdish artist’s daring Istanbul show

Zehra Doğan spent nearly three years in Turkish jails and smuggled out her works as dirty laundry

An exiled artist who spent almost three years in jail in Turkey is shining a light on Kurdish feminism with a daring exhibition of works she created while behind bars.

Zehra Doğan was among the thousands of people who have been caught up in arrests and detentions in Turkey since the 2016 attempted coup against President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s government. Those detained are accused of either supporting the Gülenist movement, blamed for the failed putsch, or the Kurdistan Workers’ party (PKK), a militant group, both of which are outlawed.

She was jailed for a painting depicting a town in the majority-Kurdish south-east of the country that was destroyed in a Turkish military operation after peace talks between Ankara and the PKK broke down in 2015.

The painting, together with her work as a journalist, led to a sentence of two years and 10 months for terrorist propaganda and inciting hatred. On her release last year, the 31-year-old left the country, and fears she will be unable to return.

“In prison, I had two choices: either to accept it, and complain, or to try to continue with my art as a means of resistance,” she said.

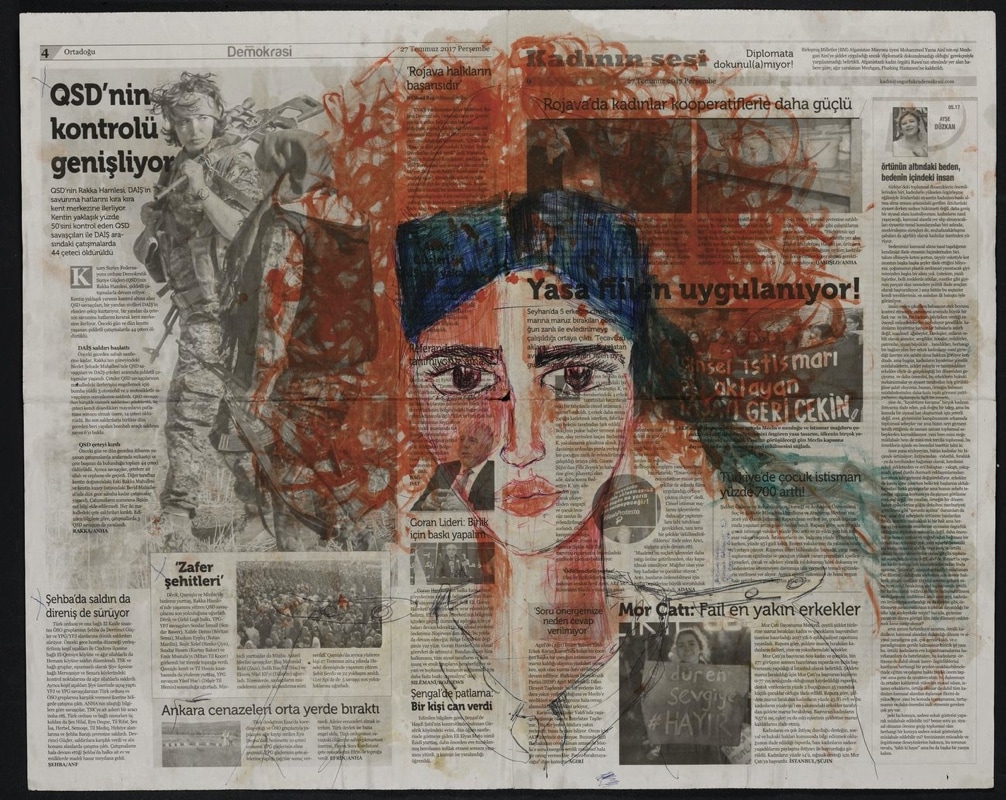

Turkish and Kurdish writers have long found their voices in prison, whereas the work of visual artists, cut off from materials and mediums, has suffered. With no paper, Doğan used newspaper, cardboard and clothes as canvases. For paint, she found that crushed herbs made green, kale was a substitute for purple, and pomegranate or menstrual blood could be used for red. Blue ballpoint pen, cigarette ash, coffee grounds, pepper and turmeric make up much of the rest of her prison palette.

The result is a striking series of works that were smuggled out of her cell as dirty laundry, now on display at the Kıraathane24 art space in Istanbul as Not Approved, her first solo exhibition in Turkey.

Women’s faces and bodies, along with Shahmaran, the half-woman, half-snake of Kurdish mythology, feature prominently. Drawn or painted on scarves and cloth, they are depicted as bound up in rope made from human hair, faces twisted in pain from childbirth or menstruation framed by traditional Kurdish clothing and jewellery.

In one piece, Womanhood, ghost-like female faces with no hair stare at the observer from the skirts of a coffee-stained dress hung from a curtain rail. It is pinned up in such a way that it looks as if an invisible wearer is dancing through the air.

The exhibition has been well received by both critics and the public. But despite its success, Kurdish art in Turkey is still struggling to find a platform.

The ruling Justice and Development party (AKP) took steps to improve cultural and linguistic rights for Turkey’s 18% Kurdish minority in 2009, leading to the flourishing of Kurdish media outlets and the establishment of the first Kurdish-language university department at Artuklu in Mardin.

Since talks with the PKK collapsed, however, many Kurdish politicians, including the leader of the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic party (HDP) Selahattin Demirtaş have been removed from office and imprisoned, and media and cultural projects have been shut down.

“Kurds have been fighting for our rights for 100 years now. Some choose to fight with weapons. We need to learn to fight through other means. For me, that is art”, said Doğan.

Leave A Comment