Historical Yılmaz Güney interview published 38 years after his death

Historical Yılmaz Güney interview published 38 years after his death

- Date: April 6, 2022

- Categories:Interviews,Rights

- Date: April 6, 2022

- Categories:Interviews,Rights

Historical Yılmaz Güney interview published 38 years after his death

"In Turkey, writers, artists, intellectuals and people who have just asked for the simplest democratic rights are in prison or in the dock (...) In Turkey, tens of thousands of Kurds are in jail just for asking for democratic and human rights for the Kurdish people," says Yılmaz Güney in an interview a month before his death.

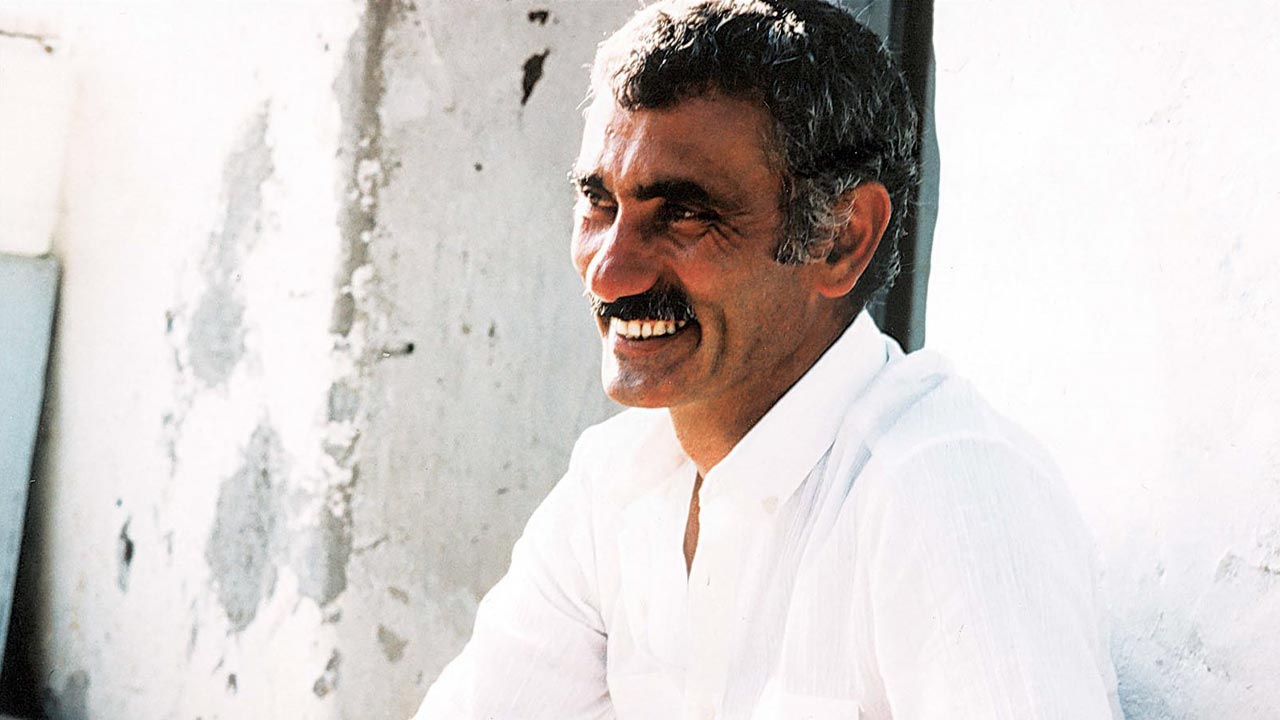

One of the last interviews with Kurdish film director and actor Yılmaz Güney before his death was published for the first time in Turkish on 31 March on the Kurdish Studies Website.

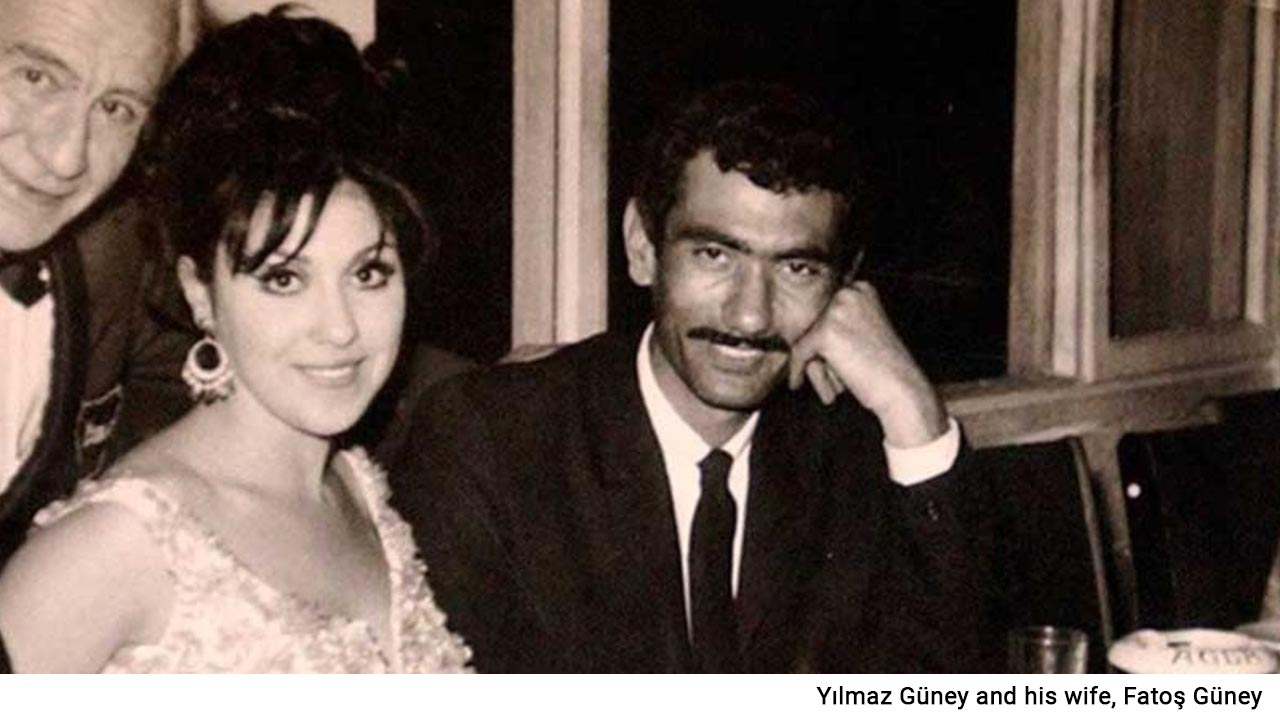

Güney, who had been incarcerated based on an allegation of shooting a judge back in 1974 and who made a prison escape in 1981 to flee to France, died of cancer on 9 September 1984, a month after he spoke to Benge.

In her introduction, Benge starts by saying:

“Yılmaz Güney spoke to me, from his exile, at a secret location in Paris on 9 August 1984. One month later, he was dead of cancer. Despite the gravity of his illness, despite the bleakness of his exile, he was desperately concerned to speak out again for the Turkish people whose voices have been stifled at home and ignored abroad. Guney himself came from one of the most oppressed groups within Turkish society, his parents were landless Kurdish peasants. So all-embracing is the official desire to obliterate the Kurds as a people that, as Guney himself said, ‘just to tell of the existence of the Kurdish people is a crime. You are punished.’

“Güney’s career – as revolutionary, film-maker, writer and Turkey’s biggest national film star – lasted twenty-six years. It was intricately linked with political events in his country, and interrupted by twelve years in prison. Prison conditions varied dramatically, reflecting the policies of the temporary victors of the power struggles between the right and centre. Güney’s third imprisonment, from 1974 until his escape in 1981, included the period of centrist rule by Bulent Ecevit (1978-9), during which he was able to write scripts in a private room and liaise with colleagues who directed his scripts in the outside world. It is in this period that ‘The Herd’, ‘The Enemy’, and preparations for ‘Yol’ were made. But even at that time, Guney was researching law books in readiness for capital charges that could be brought against him as a result of ‘associating with Kurds’. Also at this time, CIA-trained fascist groups initiated a period of terrorist attacks which snowballed into massacres by groups of both right and left. Guney admitted he was safer in jail than out.”

Below are some of Benge’s questions and answers by Güney, most of which sound more of a depiction of the current social and political circumstances surrounding Turkey rather than echoes of a distant past.

The reader should also bear in mind that even the political administration and the regime of the mid 1980s are not really ‘things of the past’ in Turkey as both the military junta’s constitution and the political structure it created 40 years ago are still essentially in place and remain to be transcended.

How has being a Kurd affected you?

I will start by telling about my origins. My parents are both Kurdish and they moved to the area around Adana from their homeland Kurdistan before I was born. To be more specific, my mother’s family moved from Kurdistan to this part of Anatolia during the First World War, because of the Russian occupation of the Eastern territories, and my father’s family moved south-west because of a vendetta. So they were migrants – not foreign migrants, but internal migrants; they moved from one territory to another. I was born there, of Kurdish parents, but I didn’t speak the language. I didn’t know the language because it is forbidden to learn or speak it. It’s forbidden to have your own culture. It’s even forbidden to have any identity. All these obstacles were put up and I had to discover my identity and origins later on. The official ideology tells me ’You are a Turk’ and I have to learn ’I’m a Turk’, despite the fact that at home my parents spoke Kurdish. I became aware of it only when I was 15 years old. But then, when I was 15 years old, when I became conscious of my origins, I didn’t have a nationalist attitude. I am not a nationalist because I had already discovered socialism – socialist ideas. In this sense of a social class basis, I am for the unity of all people and not for one particular nation. On the other hand, in answer to your question, I feel that being a Kurd has had a great influence and it explains many characteristics and particularities in me.

The Kurds, because they were landless and poor, had to move to regions where they could find jobs. They had to work, it was rather like an interior migration and, like the migrant workers that you have in Europe, they have the toughest and the meanest jobs and have no consideration because they are at the lowest scale of society. In Istanbul, for example, 90 per cent of porters, who carry extremely heavy weights, and street-cleaners and the ones who clean public washrooms, all the dirtiest jobs are done by Kurds. They have the toughest jobs, the worst jobs and they get no consideration, just humiliation. Humiliation to such a point that to say ’Kurd’ is an insult in the Turkish language. And when they go for military service, which is very long in Turkey, there again they have the worst jobs – they aren’t trusted. So, at every opportunity, on the pretence that they’ll riot, their guns are taken away and they are sent to cut onions. So this, of course, has an influence on any person who has Kurdish origins. But, to be honest, there are Kurds who also have extremely high positions in society, who are in the highest ranks of the state apparatus – but that is because they never say ’I am Kurdish’. They hide it.

If you don’t admit you are Kurdish, you can go very high. You can be a minister, a deputy, a member of parliament. But once you admit it, even if you have such a high rank, you will still go to jail. There are now some deputies in jail just because they once said ’I am Kurdish’. So, one shouldn’t say they are Kurdish deputies, because they are not elected as Kurdish deputies. They are elected as Turks living in a country that no one can admit is Kurdish.

There are now twelve million Kurds in Turkey, but the Kurdish population is dispersed all over the country. Not only do they have to move west to hunt for jobs in the cities there, but, after the First World War, there were also enforced migrations. They took whole villages and people from whole areas and they moved them to another part of Turkey. Even on the westernmost border of Turkey, you will find Kurdish settlements. You could call it internal exile. They were sent in exile to other parts of the country. Forced settlements, parallel to the forced migration to find jobs.

What is going on in Turkey?

To understand what’s happening, you have first to take into consideration the general contradictions and rivalry between the two superpowers. The actual Turkish administration depends, of course, on the US – on American imperialism and its local collaborators, the bourgeoisie with capital. The ruling coalition is the military and bureaucrats, soldiers and high civil servants. Evren, the President, represents the army, and Ozal, the Prime Minister, represents the technocrats. Their aim is to transform the country into a paradise for plunder – and they have succeeded in this. Also, they reinforce the position of American imperialism, not only within the country, but within the whole region. A handful of people get richer every day, while the condition of everyone else gets worse every day. The opposition – workers, peasants and intellectuals – is muzzled and repressed. All media, artistic creation and expression are completely controlled. There is a complete monopoly on all information, which is totally onesided. No information is allowed about the political situation, the economic situation and what is happening in Turkish jails, where thousands are imprisoned for political reasons.

In the West you will hear a lot about what goes on in Poland, Afghanistan, East Germany and so on. US imperialism wants to block certain alternatives. The US says it happens in the eastern bloc so it can happen in Turkey. It happens there … It happens in Turkey, ’that’s normal’. The correct democratic attitude is to oppose any assaults on democracy in any part of the world, wherever they occur. It must be emphasised that western intellectuals, the public and ostensibly democratic states and administrators pretend to be democratic but condone fascist regimes and therefore become accomplices. I’m not afraid to say this. For instance, the Thatcher government talks about democracy in its own country, and abroad it supports Turkey. This just won’t do. Whenever, in Poland, the leaders of ’Solidarity’ are persecuted, the western world follows the situation and expresses its indignation. In Turkey, hundreds of labour leaders are on trial on capital charges. In Turkey, writers, artists, intellectuals and people who have asked for the simplest democratic rights are in prison or in the dock. In Turkey, members of the Peace Association have been sentenced to five to ten years. In Turkey, tens of thousands of Kurds are in jail just for asking for democratic and human rights for the Kurdish people, or just for saying ’I am a Kurd’. In Turkey, thousands are on trial, threatened with the death penalty. Tomorrow, probably mass executions will come on the agenda as a result of these trials because of these capital charges. There are no voices raised, there is silence. We believe that this doesn’t correspond with democratic tradition.

Even worse, they say there is democracy in Turkey because a parliament exists. This is a very strange kind of parliament. Most parties were excluded from the elections. Not just the workers’ parties, the socialist party and the communist party – because they were all locked up anyway — but even the centre parties who had the slightest disagreement with the military were banned from participating. Commentators who say there is democracy ignore the fact that this is the basis on which this parliament was founded. The junta decided who could stand and also appointed the person who was to form the official opposition.

Who will bring about progressive change in Turkey, and how?

Let’s come to what we really want. We are demanding a democratic republic. What we understand by a democratic republic will be independent from the US, and from the Soviet Union. It will be independent from any imperialist nation, in no military camp, and will recognise freedom for all political movements within the nation, and will recognise national and democratic rights for all nations within its body. A real democracy. We are fighting for these demands for a democratic republic.

Today, in Turkey, we don’t have the conditions for a socialist revolution. The step forward is simply the struggle for a democratic republic, and we should treat the whole question from this basis. There are no genuine social democratic parties in Turkey. The Populist Party in parliament operates within the fascist constitution. SODEP, the Social Democrat Party, which legally exists now, but isn’t in parliament, will change nothing. The plight of the Kurdish people won’t change, the people’s situation won’t change, the structure of the state won’t change, there will be no change in political or human rights. Perhaps some minor tinkerings, but the essence would remain the same. For the creation of a genuine democratic republic, it’s going to be necessary to educate the working classes towards these ends. This can’t happen overnight.

Today, Turkey is one big prison, and for this prison to be transformed into freedom, to be able to smash these walls and return to genuine democracy, the responsibility belongs to revolutionary democrats. If we can create close links with our people, we can actually succeed in this task. Otherwise, we will end up just singing interminable songs of hope. We have to admit we aren’t sufficiently prepared right now. What happens now, in Turkey, is that people have aspirations and expectations and sometimes they fight – but what for? A different jail, a better jail. When there was direct military rule, Evren said he would give the people a new military parliamentary regime. That was another jail. People said, ’Perhaps, perhaps it might be better’. So they voted for it. That was the story of ’The Wall’. The children in the film were in a horrible jail. When they riot, they don’t even think about freedom, about liberation, they just dream of a better jail. ’Perhaps’, always ’perhaps’. ’Maybe this one will be better’, and we see the result. So the Turkish people said, ’Maybe the civilian administration will be better’.

And now they are looking for some other ’perhaps’. ’Perhaps SODEP will be better.’ But with this ’perhaps’, we will never get anywhere, we will never have freedom.

To the British public, and intellectuals. I appeal to you on behalf of my friends and democrats in Turkey.

To show more sensitivity to what is going on in Turkey.

To show more concern about the torture in its prisons, and the executions.

To support the demand for a general amnesty.

To show more sensitivity to the Turkish intellectuals who are being punished.

To pay special attention to the oppression of the Kurdish people, because they have double oppression, a national and a class oppression.

The repression in Turkey is not ’just happening in Turkey’. It is happening to democracy in general. We have to shoulder this responsibility jointly.

* The interview was published in Race & Class in January 1985.

Leave A Comment